June 6, 2022

Inflation at the Gates

this year I set out the case for why the American consumer is seeing inflation at the highest levels since the 80’s (see article titled “Kindling for the Inflation Fire”). Fast forward a few months later, and we’re still in a high inflationary environment. But, rather than continue to spend time discussing the cause of inflation or ways the Fed could fight it, I figured it would be worth our time discussing issues we can actually control. So, here is a definitive list of assets and how they behave under inflationary environments.

In this newsletter, I will cover cash, bonds, and the general stock index. There will be a part 2 where I will break down specific stock sectors.

Real Interest Rates, Returns, and Time

Before we get to that, though, a bit of background is needed. When discussing inflation, there’s a need to distinguish between nominal return and real return. Nominal return is the interest rate or return earned on an asset before inflation. Real return is the interest rate or return earned after inflation. Basically a 5% nominal return with 2% inflation produces a 3% real return. Your spending power increased 3%. This is the true goal of investing, to increase or maintain your spending power over time.

Savings accounts & CD’s (cash)

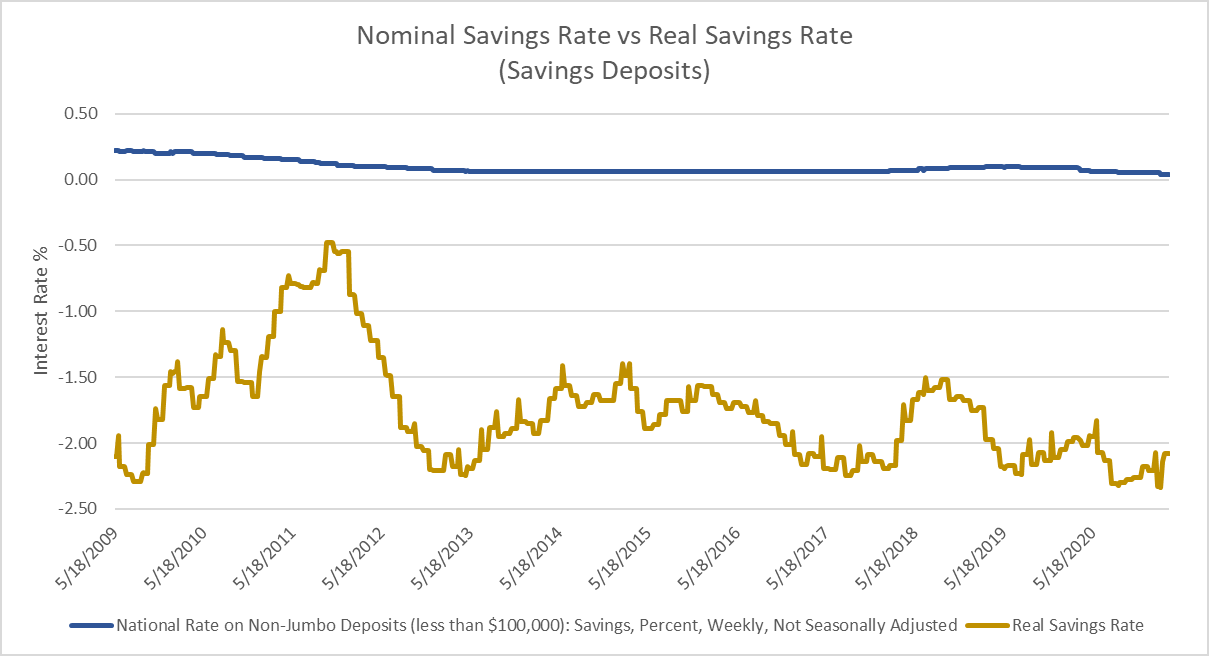

Essentially my entire working career has been in a zero-interest rate environment since graduating college in 2008 when savings accounts and CDs barely produced any return. Fortunately, inflation hasn’t really been an issue either. However, real returns in savings accounts were still negative the entire time since the Global Financial Crisis.

Calculated from FRED, St. Louis Fed (1).

Whenever the Federal Reserve (and banks by default) are loose with monetary policy, that means interest rates are low because they’re trying to spur growth. Growth begets inflation and thus, savings accounts typically produce a negative real interest rate, eroding your buying power over time. When monetary policy is tight, that’s when you typically see positive real interest rates on savings accounts. But those are conditions we haven’t seen for decades now.

As a result, cash and cash equivalents are among the worst methods of saving for future spending during inflationary environments until monetary policy begins to tighten.

Treasury & Corporate Bonds

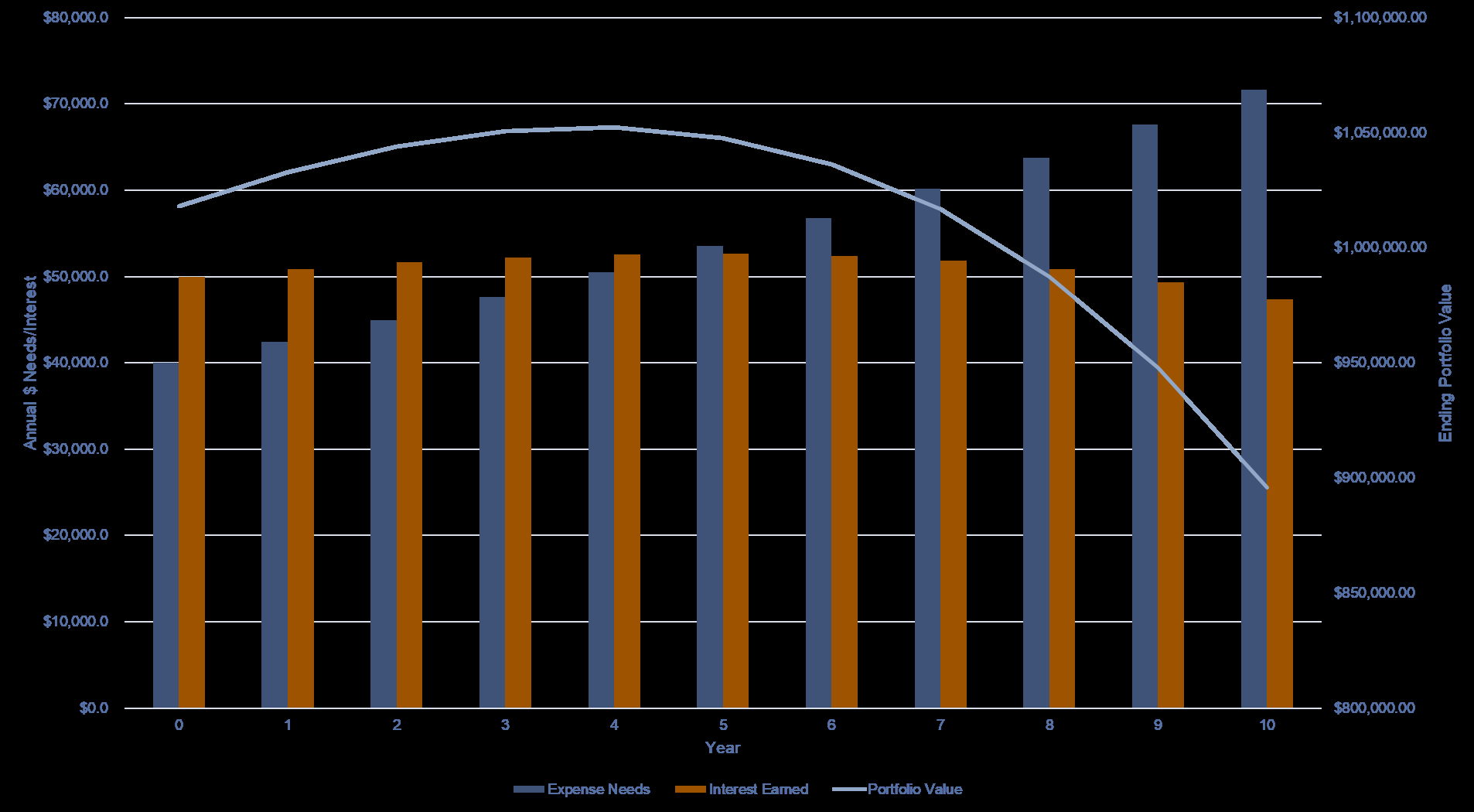

The key idea with bonds is that they lock in your income (interest) for the lifespan of the bond. Therefore, buying a default-free bond yielding 3% is very closely going to return about 3% if held to maturity. That 3% return is your nominal return. As long as inflation stays below 3%, then you’re earning a positive real return. When that inflation grows above the nominal yield, then real returns will be negative for bonds.

To illustrate this, assume a $1m bond portfolio with 5% interest satisfies the living expenses for an individual who needs $40,000 per year. That portfolio provides $50,000 of annual income and the remaining $10,000 of interest gets reinvested back into the bond portfolio. But, inflation is 6% per year, outpacing the return earned by the bond portfolio. By year 5, inflation will have outpaced the interest earned on the bond portfolio and the individual will start drawing down the principal rather than living on the interest. In this case, inflation is actively eroding this investor’s spending power.

This is why bonds tend to sell off during inflationary environments like the 1970’s, 1980’s, and so far in 2022. Unless you’re invested in inflation-protected securities like TIPS, then your purchasing power can be eroded by holding bonds through an inflationary environment.

Stocks

Stocks tend to go up with inflation, except for extreme cases. Since 1993, the correlation between monthly core inflation and price increases in the S&P 500 is 88% with a 77% R-squared and a very low P-value (2). That’s a fancy way of saying stocks tend to rise with inflation.

The reason for this is pretty simple. Corporations tend to pass through costs to the end customer. If input costs go up $1, corporations tend to raise the price on their goods or services $1. This increases earnings and long term, stocks follow earnings. Thus, as inflation increases, so does earnings, and so does stock price.

There is a cutoff though. Typically, when inflation reaches year-over-year rates of 12-14%, then corporations can no longer increase prices to keep up with inflation without destroying demand from their customers. Plus, there’s the secondary effect of rapid Fed intervention that can dry up liquidity in the stock market and pop any pricing bubbles in the process.

But since 1993, core consumer prices rose 92.2% or 2.26% annually while the S&P 500 had an annualized nominal return of 8.31%. Thus, the real return for the S&P 500 was just north of 6%, annually (2). This includes the Dotcom bubble, the Global Financial Crisis, the COVID-19 Pandemic, and the inflation we’re experiencing today. Therefore, stocks make a great, long-term option to maintain one’s purchase power.

Final Thoughts

None of this is a “one size fits all” approach to investing in inflationary environments. Time plays a critical role here. The longer the investment horizon, the more inflation plays a role in real returns. But, the reverse is also true. Short investment horizons should ignore inflation all-together because volatility is much more critical to reaching that savings goal. On a one-year time horizon, stocks can and have lost as much as 40% in value. A 40% loss is significantly greater than any one-year loss in buying power from inflation. Thus, the best course of action for those short investment horizon goals is probably either bonds or cash simply because the inflation doesn’t offset the need for safety.

Ultimately, the longer the time horizon, the more inflation erodes your spending power, and the higher nominal returns you’ll need to offset that spending power erosion.

Sincerely,

The Signature Wealth Management Team

3625 Cumberland Blvd. SE • Suite 1485 • Atlanta, GA 30339 • 678.932.2500